"We are women, we are many, we are half of humanity, we want half of the power. We must end patriarchy before patriarchy destroys the world." (1982)

The "Women's Initiative October 6" (FI) was founded in the former federal capital Bonn as a non-partisan and supra-regional women's alliance after the Bundestag elections on October 5, 1980. Once again, the proportion of female members of the Bundestag was below 10 percent - today it is 35 percent - and women's issues played only a subordinate or even no role for all parties. In this situation, it was necessary to create a more powerful women's lobby. Margret Meyer, founding member of the FI, writes: "The women (had) to realize that, on the one hand, they were once again miserably represented in the new parliament and, on the other, that nothing remained of the fine election promises made by men to women. The women wanted to turn the anger in their stomachs over this realization into creative work with the goal of new strength and power for political change."

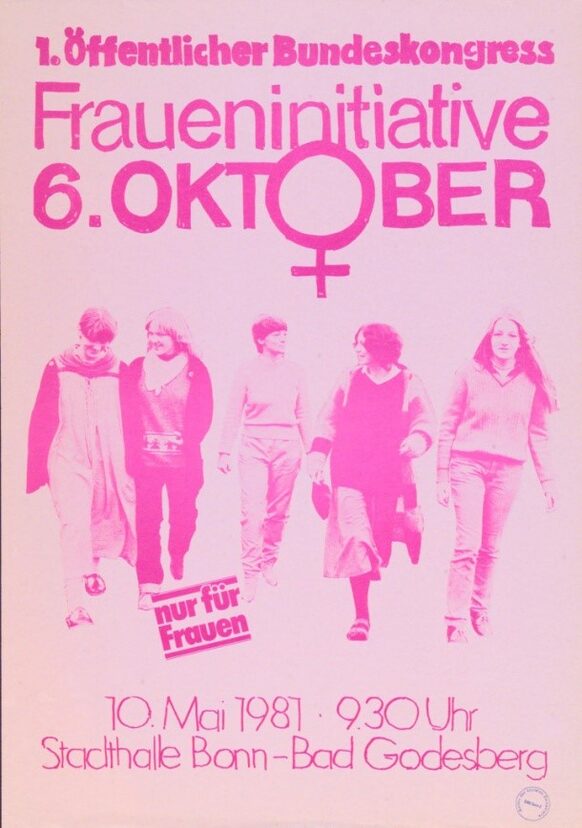

The FI held eleven national congresses in Bonn, each of which was attended by several hundred women from all over Germany. From 1981 to 2000, the information service IFPA (Initiative Frauen-Presse-Agentur) was published. This provided over a thousand multipliers throughout Germany with information from the women's sector every month. It was "an attempt to highlight a piece of counter-publicity for women", but also served as a "means of communication for the network that the women's initiative wanted to establish", writes Margret Meyer, editor of the IFPA for many years.

(1982)We don't ask whether something is reformist, radical or revolutionary, we ask whether it is good for women or bad for women.

Creation of the Women's Initiative October 6

The emergence of the FI has its roots in the women's movement. This began in the early 1970s with the "Bonn Women's Forum", which saw itself as part of the newly emerging autonomous women's movement. More and more women were getting involved in small groups at the time, fighting vociferously against Section 218, meeting in theory and action groups or in counseling and self-awareness groups. For years, the center in Endenich Straße was the place to go for the many women - old, young, students, pensioners, singles, divorced, straight and lesbian. It was all new and exciting, like a great political awakening for some. "The private sphere is political" or "Women together are strong" were slogans from that time, and many believed that a feminist revolution could finally make society more women-friendly.

However, after just under a decade of struggle, it became clear that although the awareness of many women had changed, the resistance of patriarchal structures, including in politics, was still immense. The women of the "Bonn Women's Forum" believed that a profound change in society could only succeed if "the totality of women became a greater political power factor" (Margret Meyer). This time had come in 1980.

On September 8, 1980, one month before the Bundestag elections, a discussion with Alice Schwarzer on the topic of "boycotting elections" took place in Bonn. While most of the women in the packed Godesberg town hall seriously wondered whether "an election boycott or a threat to do so could finally persuade the social-liberal rulers to better represent women's interests in the future", women from the Working Group of Social Democratic Women (AsF) accused Alice Schwarzer of unpolitical behavior, according to Hannelore Fuchs, founding member of the FI. When an article appeared a few days later in the SPD press service with the headline "The goat as gardener" with angry attacks against Alice Schwarzer, politically active women in the German capital, including committed SPD women, thought that enough was enough.

There were a number of personal contacts between feminists from the "Bonn Women's Forum" and SPD women who wanted to make a difference. They came together around the idea of creating a nationwide women's network and decided to make the day after the election, October 6, a signal for the fight for women's power. To this end, they invited people to a coordination meeting at the "Kessenicher Hof". What was new was that women from the autonomous women's movement of the "Bonn Women's Forum" and committed trade union and party women overcame their mutual reservations and joined forces. Hannelore Fuchs describes the mood as follows: "The fight and enmity between party women and feminists must end, as must the fear of contact between them. Many of them have been caught between two stools for a long time anyway: for their party comrades, they are colorful chickens with their far-fetched feminist ideas; for the movement women, as party women, they are always suspected of helping to run the men's business."

Manifesto of the free woman and strategic issues

In May 1981 and May 1982, the FI organized two national congresses (1), (2) in the Godesberg Stadthalle. These meetings of 400 to 500 women each were characterized by euphoria and a spirit of optimism. The aim was to adopt a comprehensive joint "Manifesto of Free Women". In the course of the process, however, it became clear that there would be no final product. When the efforts finally resulted in the "workshop paper", it stated: "It is not yet finished and may never be finished. Many of the demands made are already widely supported, while the controversial issues are still being discussed. The paper is internal working material of the initiative, which is available to all women. Every woman is called upon to continue working on it."

The preamble to the "workshop paper" emphasizes the goals of the FI: "There must be an end to the rigid division of roles between men and women, [...] to the division of tasks according to which men are responsible for work and women for the home and children, and [...] to the resulting assessment that what men do is more socially valuable and necessary than what women do." The openness of the FI was demonstrated by the fact that every woman was invited to take part. "We want to work with every woman who is dissatisfied; who has critical thoughts about today's reality; who feels the strength within herself to want to change something; who wants friends with whom she can change something together; who wants to develop alternative ways of living and working; who is out of step with the institutions; who wants to prevent our lives and our freedom from being increasingly restricted; with every woman who feels the effects of a misogynistic society, we want to change the situation."

On the 32 pages of the "workshop paper", the positions are presented in the individual chapters: Discrimination in language; Role models in school textbooks; Girls and women in education and training; Women in working life; Women and modern technologies; Women and the public purse; Women and sexuality; Women and housing; Lesbian manifesto; Developing new ways of life as an alternative to the previous family situation; We don't just need different role models, we need a different evaluation; Women's health care and medicine, violence against women; Media are still a man's business; Foreign women in the FRG; Pension reform 1984; Anti-discrimination law; Women and peace. The "Workshop Paper" was an impressive attempt to bring together the entire spectrum of demands of the New Women's Movement. When there was no unity, such as with the so-called "Mothers' Manifesto", dissent was expressed.

At the beginning of the FI, the focus was on strategic issues in order to ensure that women in the Federal Republic became a power factor that no one could ignore. The FI was not intended to create a feminist party, an association or an umbrella organization for women, nor was it intended to create a new women's group that would set itself apart from existing women's groups. The aim of the FI was to coordinate existing women's groups. By networking contacts and information, the aim was to create the possibility of carrying out effective joint campaigns throughout Germany. The issue of power was discussed in detail at the 1st Congress. But instead of discussing concrete strategies for gaining power, the danger of abusing power was immediately conjured up. The result of these debates was that the FI dispensed with a tight, hierarchical, party-like structure and did not elect a board or spokeswomen. Heidi Baumann, a founding member of the FI, describes this in a vivid image: "We wanted to work like rhizomes, namely as 'weeds' whose roots spread underground and continue to branch out, even if they are constantly plucked from the surface."

In order to be able to carry out the many organizational tasks, a professional office was first set up provisionally in the Women's Museum, then in Kirschallee 6. All expenses, as well as the salary of the managing director Sylvia Fels, were financed by donations and membership fees from the "Association for the Promotion of Civic Education and Participation of Women".

Women against reaction - women's counter-reaction

On October 1, 1982, the social-liberal coalition came to an end. In a vote of no confidence in the previous government, the FDP, together with the CDU, elected Helmut Kohl as Federal Chancellor. The latter called for a return to traditional values and saw the change of government as a "spiritual and moral turning point". The FI reacted to this political development. It feared massive setbacks for women's rights. In November 1982, a special meeting entitled "Women against reaction - women's counter-reaction" (3) was convened at short notice in the Women's Museum. This was followed in June 1984 by the federal congress "Expose the men of change!" (4). The invitation stated: "At our last congress in November 1982, we could not have imagined how totally a black government would destroy the small successes of the last decade. We are now experiencing on a daily basis how everything that we have laboriously held on to for a few years is being ripped out of our hands through many back doors. But we also see that hundreds of thousands of women do not realize this."

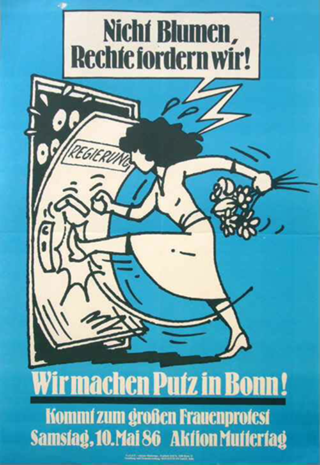

In order to protest against the conservative women's policy in a public way, representatives from the women's movement, politics, culture and trade unions had forged a strong women's alliance and called for a nationwide "Mother's Day Action" on May 12, 1984 under the motto "Not flowers - we demand rights!". The FI was one of the first signatories of the appeal and one of the organizers of the demonstration, to which 15,000 women from all over Germany came to Bonn and presented their demands on the Hofgartenwiese. Despite such successes, Heidi Baumann remarks: "Nevertheless, at our 4th Federal Congress we didn't really want to believe in our counter-power. Everything went much more slowly than we thought." But the FI women still had enough strength for further protest: Against the NATO Double-Track Decision, 108 self-made, shiny silver Pershings were carried through the German capital and unfurled as pink penises in front of the Ministry of Family Affairs.

The question of alliances, which was the subject of heated and controversial debate, took up a great deal of space at the two "Wendekongresses". Some argued in favor of the strategy of new alliances: The effectiveness of limited alliances on common demands, the definition via commonalities, the prevention of the women's movement becoming isolated, new experiences in joint action. The other side argued against alliances with established political groups: Watering down radical women's demands into compromises, giving up the autonomy of the women's movement. The establishment of a "women's council" was also considered. The FI declared: "If a women's council were to be created, it would only be composed of many groups, well organized and with the basic ideas of the FI 6th October, although the initiative cannot and does not want to take on this function!"

And yet she moves - women's movement in dark times

In the mid-1980s, the FI's commitment to women's rights finally began to bear fruit. Although the successes had not yet manifested themselves in more women-friendly laws, the women's issue was moving to a more central position in people's minds - including those of men. Hannelore Fuchs wrote in 1986: "We actually have a lot of reason to be satisfied. The situation for women in the Federal Republic has deteriorated considerably in terms of real opportunities. [...] Nevertheless, it cannot be overlooked that men are beginning to understand the explosive nature of the women's issue". The invitation to the 5th Congress of the FI in 1985 also registered progress: "Not only we feminists, but also women in parties, trade unions and associations are more active than ever before and are in broad agreement on many points." For the 1987 Bundestag elections, the SPD launched the campaign "Every fourth candidate a woman candidate". In 1986, the Greens decided on minimum parity for all their committees and electoral lists. In 1985, the CDU organized an entire party congress on the topic of "women".

The minutes of the 6th Congress show that the public could no longer ignore the FI, invitations to hearings were increasing, newspapers announced the congresses and reported on them later. In addition, more and more Equal Opportunities Offices were being set up at municipal level.

This was preceded by numerous witty and imaginative actions initiated by the FI, some of which were supported by broader women's alliances. On March 8, 1985, International Women's Day, "Black Brides" demonstrated against the misogynistic new regulations in divorce law. In 1985 and 1986, the second and third nationwide women's demonstrations took place in Bonn for the "Mother's Day campaign". The symbolic occupation of half of the council seats at the constituent meeting of the newly elected city council in Bonn in October 1985 reaffirmed the demand for quotas.

In 1985 and 1986, the FI organized the two national congresses "And yet she moves - women's movement in black times" (5) and "Rainbow feminism: black, red, green, blue/yellow - who benefits from the women's movement?" (6) with around 200 participants each. The FI women partly explained the halving of the number of visitors to the congresses compared to the early days by the fact that there were now more opportunities for women to get involved in feminist activities elsewhere than in the FI. It could not be overlooked that the FI's leading middle-aged women were not being joined by young women, as the Bonn women's newspaper Lila Lotta 12/1985 commented: "FI: Initiative of the Middle Ages? Where is the new generation?"

The 5th Congress focused on the question of alliances. Women from a wide range of groups (German Women's Council, DGB, Greens, SPD, Women for Peace, Association for Political Women's Education) were invited to clarify how far and with whom cooperation on women's issues was possible. The discussion revealed a great willingness to cooperate, which had increased considerably since the beginning of the FI. The minutes state: "In principle, we seek cooperation with all women. In some areas, we are also prepared to form alliances with non-feminists." "Experience teaches us [...]: Non-feminists also change in the course of their work."

According to Heidi Baumann, the preparations for the 6th Congress were "under the impression that the established parties had included feminist demands in their party programs." The question was how this should be assessed. The event opened with a "fish-pool" debate, in which every woman could take part, on the question "Man is feminist - woman is content?". Instead of a podium, the next day there was a round table discussion in which all the women sat in a circle with the experts in between. With this more personal exchange, the FI tried out less hierarchical forms of communication, which was well received by the participants.

On November 21, 1987, the FI organized the special congress "Women and AIDS" (7) in the Beethovenhalle with around 600 participants.

FI national congresses - feminist source of strength?

This was followed by four more national congresses: "Lila Lüste - feminist illusions and the reality of private happiness" (8) in 1988, "Eigenständig-Eigenwillig-Eigenartig - Suche nach weiblicher Identität als Herausforderung" (9) in 1989, "Einbruch-Umbruch-Aufbruch - Frauen-Generationen heute" (10) in 1990 and "Berührungsängste von Lesben und heterosexuellen Frauen in der Frauenbewegung" ( 11) in 1991. The FI no longer carried out any political campaigns.

The archive documents contain a statement by Barbelies Wiegmann, a founding member of the FI. She says that she had become increasingly aware "that patriarchy is both in society and in us women, and that every woman must first overcome the patriarchy within herself." This already indicated the direction that the FI would take with its last four national congresses, away from women's politics and towards a more intensive reflection on one's own identity as a woman and the relationships between women. Heide Baumann writes: "We see our work in the FI and for the FI as a source of our strength to live against patriarchy." Not all FI women were happy with this development. The writer Herrad Schenk, a founding member of the FI, said that the 10th Congress was "a little too psycho" for her, and that she would have preferred to talk about concrete counter-strategies against the efforts of a "right-wing majority" to reverse the progress made in women's politics in recent years.

In the invitation to the 8th congress, the FI women assume that feminist utopias are not limited to the establishment of company kindergartens, the reconciliation of work and family life as well as women's promotion plans and equality bodies. Instead, the congress should focus on the life of the individual woman, her search for sources of strength and private happiness.

At the 9th congress in search of female identity, the question of how to combine the private and the political was also raised. There was a lot of very positive feedback: "A really great atmosphere of being able to confide in each other, a natural willingness to help, warm-heartedness - of being accepted. Certainly a source of strength on the way to recognizing inner freedom. I got a lot of impetus to think about my own past and my identity." But also criticism: "Dear women, the sentence: 'The private is political' was beautiful and true and moved a lot 20 - 15 years ago. But [...] anyone who doesn't file this sentence away now is using it as an excuse for lazily remaining in old women's corners. Sexuality, body and soul are certainly essential for women, but not politically relevant at every historical moment. Where is the courage to take risks in thought and action, to be provocative, where is the enthusiasm and brilliance?"

The reunification of Germany took place on October 3, 1990. Women from the FI had already met with women from the GDR at a conference entitled "Germany - a united motherland - a new beginning or a setback for women?" in Rösrath near Cologne. Some women from the new federal states therefore also came to the 10th Federal Congress in November 1990, which dealt with typical breaks in women's biographies. They complained that they were often patronized by West German feminists and that their life experiences were not taken seriously.

The 11th and final federal congress dealt with the unspoken tense relationship between lesbians and heterosexuals in the women's movement. According to the invitation to the congress, lesbians, who made up a large proportion of active feminists, often regarded straight women as "semi-feminists" because they were dependent on men, while straight women often saw lesbians as "exotic" and distanced themselves from them because they had internalized the prevailing social view of lesbians. The hitherto tabooed separation from each other prevents rapprochement on a personal and political level and must be broken down.

Conclusion

In the 1980s, the FI made a significant contribution to breaking down the shyness between autonomous and party women, which enabled the women's movement to influence the policies of the established parties and to bring feminist ideas and women's political demands to the public. The fact that women have achieved so much in this decade is not only, but also thanks to the "Women's Initiative October 6".

However, the FI did not only gain recognition. Although it saw itself as part of the autonomous women's movement, radical feminists often met it with suspicion and condescension. Although the FI had the same goals as the autonomous women's movement, it believed it could only achieve them through broader alliances.

It is a remarkable achievement that a core group of around twelve women in Bonn managed to network all women across Germany who were concerned about women's politics and to initiate important discussions that were long overdue. It is also admirable that the activists maintained their extraordinary commitment for decades. They certainly drew courage, strength and perseverance from the close, friendly relationships between them. Even today - after more than 50 years - they are still connected. They have maintained their first fortnightly, then monthly meetings over the years, at which they exchange ideas personally and on current political and feminist issues.

Text: Ulrike Klens

References

The rights to the above text are held by Haus der FrauenGeschichte Bonn e.V. (opens in a new tab)

- Conversation with Margret Meyer on 27.07.2022.

- Heidi Baumann: On the anniversary. Our history (1991), in: The new women's movement in Germany. Farewell to the small difference. Selected sources. Ilse Lenz (ed.). Wiesbaden 2008, pp. 515-517.

- Margret Meyer: Women's Movement in Bonn. Lively and troublesome. From the Women's Forum to the "Women's Initiative October 6", in: Die Bonnerinnen. Scenarios from history and contemporary art. Women's Museum (ed.). Bonn 1988, pp. 182-186.

- Hannelore Fuchs: Fraueninitiative 6. Oktober, in: Feministische Studien. Politics of Autonomy. 5th year. Stuttgart 1986, issue 2, pp. 121-123.

- What next for the SPD and women?, in: Emma 12/1980, p. 23 f.

- The SPD and the betrayal of women, in: Emma 11/1980, pp. 15-21.

- A document, in: Emma 10/1980, p. 32 f.

- Minutes and workshop paper of the federal congresses of the Women's Initiative October 6 (1981-1991), in: Archiv der sozialen Demokratie der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.