At a time when women were only seen as servants, Berta Lungstras owes her success to her attitude of seeing herself as an instrument of God. This meant that men could also support her without being suspected of being at the service of a woman. Nevertheless, she knew how to assert herself energetically and purposefully, all the more so as she herself believed she was only acting on a "higher" mission. She never had the slightest doubt about this. She only turned her attention to the emancipation of women within the framework that corresponded to her goals, namely at the beginning of her work to raise morals and with growing insights to raise the standing of women in general.

However, she was not interested in supporting women's struggle for more political influence. Her remarkable spiritual development was based exclusively on the experiences of her work, which she knew to be in absolute accordance with the Bible. The fact that she freed herself from all bourgeois restrictions in the course of this development deserves special mention.

Childhood and youth in Wahlscheid

Berta Lungstras was born into a pietistic family. Her mother's ancestors had held the office of pastor in Wahlscheid for 350 years. Her father Carl Lungstras then became a pastor in Wahlscheid. According to her biographer, she was a true child of the Bergisches Land: "practical and sober, agile with the cheerful entrepreneurial spirit of the Rhinelander, coupled with the strong will and tenacious perseverance of the Westphalian".

She is said to have been an attentive schoolchild who loved learning. In 1848, at the age of twelve, she lost her father, to whom she was very attached. Her spiritual instruction was continued by his successor, Pastor Korten. She was particularly devoted to her teacher Wellenbeck, who later supported her actively and ideally in her "work". She was particularly encouraged musically. Concert and theater visits and lectures were a matter of course.

Music in particular made a great impression on the sensitive girl. She spent a year at the Reinold family boarding house in Reusrath, where a serious Christian spirit prevailed. There, too, she took every opportunity to learn, and was particularly interested in languages and music.

Care of the poor and sick

In 1858 - ten years after their father's death - her brother was already working as an entrepreneur in Mülheim. Berta's older sister Emma marries her cousin Wilhelm. Berta remains close to her cousin throughout her life and receives much legal advice from him. Berta and her mother move to Bonn with her. As was customary in Christian middle-class circles, the family members became involved in social work. It is a matter of course for them to care for the poor and sick in the community.

Berta helps in the hospital during the 1870/71 war. The misery of the soldiers leaves a deep impression on her. She was heading for a personal crisis, as she now felt that her life was unfulfilled in the face of the misery in the world. She refers to the Bible verse: "I did this for you, what will you do for me?" She experiences her first deep friendship with Sister Auguste, a Kaiserswerth deaconess, with whom she discusses her problems in detail. As she writes in her diary, she wanted to continue on her path quietly, be more independent of people, withdraw more and more from domestic and social duties and not rely on understanding from her family, in accordance with the Bible verse: 'Be doers of the word and not hearers only'. And she continues: "We chatted away pleasurable hours, although a feeling of unease hardly leaves me when I think of what I could do during this time, even when sitting idle like this". However, she realizes that she is not suited to being a parish deaconess because of her lively temperament and independent nature.

She spends the summer of 1872 in Mühlheim. She persuades her sister-in-law to found an association for women who have recently given birth. Back in Bonn, she is active in hospital and community work, i.e. she receives care orders from the community, the deaconry, via Prof. Nasse. She sells her own valuables for the winter donation and organizes the Christmas presents for the poor with great success.

In November, she receives permission from Professor Rühle's wife to visit the clinic for the first time, with the approval of the clinic director. He also introduced her personally when she made her first visit to the clinic in April 1873. Another supporter at this time was Princess Reuss XIII, who was impressed by her organizational skills.

Encounter with unintentionally pregnant girls

In March 1873, a "fallen" girl came to her for the first time and asked for help. At the time, these unwanted pregnant girls were admitted to the clinic for twelve days to give birth and then left to their fate. As a result, the infant mortality rate was extremely high. Twice Berta rejects such an "immoral" request (to deal with such a sinner), but the third time she has doubts about the alleged "depravity" of these girls. Through her friend and advisor, Sister Auguste, the girls are helped.

She began to look after these young women and placed them in Kaiserswerth (the motherhouse of the deaconesses founded in 1836) and back in their families. The children were taken into care separately. However, she learned from this experience that it was healthier for everyone if the children stayed with their mothers. She seeks and finds support from professors and clergymen.

Foundation and expansion of a supply house

In July 1873 (she is almost 35 years old), she publicly admits to her idea of a supply house, which she has been developing with her friend, Sister Auguste, for several months. This was a scandal in these social circles! She later said that she was convinced that her life only began once she had found her job.

As early as August, she signs the rental contract for a simple house without water and sewerage at Maxstraße 1 in Bonn, against her mother's resistance. Two women with their children and an orphan boy moved in. Due to her tireless advertising activities, in which she finds great support from Princess Reuß, the Montagverein is founded, which sews and mends for the supply house. Her mother is now involved, she has changed her mind. Berta herself is energetic in every direction: she moves old furniture, paints others, does carpentry, takes care of the septic tank, etc. From September onwards, she publishes regular annual reports, which become a model for a further eighteen care homes in the German Reich and neighboring countries. The timing was clever, as it allowed her to refer to the work she had done for a winter or Christmas collection.

Her mother moved in with her eldest daughter in Quantiusstraße to renovate her parents' apartment and Berta was able to move into the supply house herself in May 74 - without offending her mother. "That's how the Lord set me free." In the meantime, nineteen girls with children were already living in the care home. Her work is recognized and the Mayor of Bonn, Kaufmann, thanks her personally.

After a fierce struggle with herself and with unwavering trust in God's help, she buys a house in Weberstrasse 69 in 1875, which offers considerably more comfort and a small garden for the children. The move takes place in April. Now she has a mountain of debt and no regular income. She has to rely on donations, but these are flowing in, also thanks to support from the best circles.

Her top priority is the moral consolidation of the "girls". If girls relapse with a second child, she regards them as resistant and lost. She no longer takes them in. In her diary, she writes: "But our house is not for girls who have drifted around recklessly, turned prostitution into a business or come out of prison. Protestants of this kind belong in Magdalene asylums, Catholics in the monasteries of the Good Shepherd." Life in her care home has the character of a large family, no coercion or punishment is used, the front door is not locked.

Naturally, however, she runs her house strictly according to Christian rules with daily prayers and devotional hours. There is also a lot of singing for psychological stabilization. She seeks professional support for Bible lessons, but is refused by the pastors. They do not want to enter such a "house of sin". Instead, she manages to get dedicated professors to come into the house.

The girls are trained in all domestic tasks, depending on their abilities, and later always find good positions in Bonn families.

In March 1876, Berta Lungstras was able to take on a permanent assistant for the first time: Berta Bernhardt, known as Berthel, on whom she can rely one hundred percent, as she carries out her task with the same idealism as the founder herself.

In 1880, Berta Lungstras inherited money and household goods from her base Caroline Lungstras (founder of the Carolinenstift). She extends the house by adding an extension and closing a gap in the building. It also gets a sewer connection.

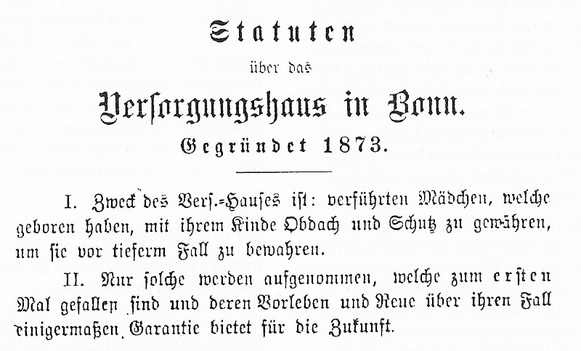

In 1882, Berta presented an annual report (the ninth) with statutes for the first time. Until then, she had avoided doing so on the grounds that each individual case required special attention. In the meantime, however, it has become clear that certain basic positions of the work remain the same.

Maternity hospital

In 1888, Berta received permission to open a private maternity hospital after she had set up a delivery room, found a midwife who lived permanently in the house, worked free of charge and was supported by an equally idealistic doctor. As is her way, she energetically pushed this project forward after disagreements arose between her and the clinic.

Her independent way of managing the medical care of the girls and their children is also remarkable. For a long time, Prof. Zuntz was her trusted doctor. However, when she found out that homeopathic treatment was gentler on the children and equally successful, she changed doctors by mutual agreement. The children's mortality rate can be further reduced.

Nevertheless, she is slandered at the town hall.

Together with the Mayor of Bonn, she negotiates a regulation that takes the wind out of the sails of such slander. All doctors work for her free of charge. Her success has many enviers here too and so she has to put up with more frequent inspections. She also has to fend off other bureaucratic requests, for example to turn her supply house into a hospital or to house the girls in large dormitories instead of in small rooms with their children. In recent years, Berta has also taken in women for training on special recommendation. She refuses to set up her own training center. Her "work", to which she has since added a children's home, is now known at home and abroad and interested people come from far and wide, even from India and Japan.

It is astonishing that Berta Lungstras always finds time to look after "her" children personally despite this immense organizational work. She plays with them, takes them on longer trips and gives them surprises. The children love her more than anything and call her "Tata" after the name of a little two-year-old. As soon as she returns from one of her trips, the best thing for her is when the children greet her with songs, poems and paintings.

Fight against prostitution

As a result of this intensive work with the young women, her eyes slowly opened to the social events behind the personal dramas. In her sixth annual report, she writes: "The heart revolts when one sees this misery. For, as it stands today: the seducer goes free, the seduced woman alone bears the guilt in the eyes of the world. In God's eyes, of course, a different measure applies; before him all men are equal. It does not say: Because you are a man, you may commit the same sin with impunity for which a woman is despised and must atone all her life ....."

She joins the International Association of Friends of Young Girls, founded in Geneva in 1877, befriends its founder Aimée Humbert and actively promotes it in Germany. The association became a branch of the German National Association. This promotional work encouraged Berta Lungstras to no longer just help individual women, but also to take a public stand against vice and immorality. She takes up the fight against prostitution. This is a big step for her, considering that for a long time in her life she had not even known about such an institution, let alone dared to speak out publicly about such an "unseemly" topic. After many battles, a number of smaller associations merged to form the "Rhenish-Westphalian Association for the Elevation of Public Morality". It was important to her to involve men in her ongoing fight against prostitution and trafficking in girls because she realized that this was the only way to give her efforts the necessary weight.

Mrs. von Diergardt gives Berta Lungstras her large house on Poppelsdorf Allee. Berta sells it and buys a small house opposite the supply house as a "home for wandering girls and drinkers". After working more intensively with this target group, she supports the movement for alcohol-free pubs. Soon there is the first mobile GOA (Gastwirtschaft ohne Alkohol) in Cologne.

Demanding social equality for women

In 1891, Berta Lungstras publishes an appeal for a legislative initiative to oblige fathers of illegitimate children to pay maintenance. This appeal was signed by 16,000 people from Bonn and sent to the Empress and the Reichstag in Berlin. However, parliament refused to debate the issue. The petition was filed under "Petitions not suitable for hearing before the plenary".

Unfortunately, in principle, not much has changed in the attitude to these issues in Germany to this day. Although men now have to pay maintenance for their illegitimate children, the general public still considers women to be inferior as a result. "Single parents" are viewed with disrespect and are not given sufficient support in any way. Especially with regard to prostitution, men in Germany go unpunished. In some countries, e.g. Sweden and France, prostitution is considered a gross violation of a woman's integrity and anyone who "maintains a temporary sexual relationship in return for payment" is punished, because sex "work" is not work like any other, but violates human dignity.

From all her experiences, Berta Lungstras concludes that it is essential to put women on an equal footing with men in society. This includes a comprehensive education, including university studies or vocational training, also in order to have an independent income. She is outraged by a sermon in which the praise of the virgin behind the hearth was sung. She invites Helene Lange to speak to her about women's education at the supply house. She turns to Luise Otto Peters in the fight for female doctors because she demands that women should carry out gynecological examinations. However, Berta rejects emancipation efforts aimed at political rights. She joins the newly founded German Protestant Women's Association, but does not take on any board work due to her age and excessive workload.

In 1893, Berta Lungstras and her friends had already set up the first Protestant hospice as a cozy guesthouse at Poppelsdorf Allee 27. This was also made possible by a donation from Baroness von Diergardt. She also founded the "Evangelical Hospice" working group, a meeting place for progressive men and women; international congresses were held there and community work was organized.

Her health suffered greatly as a result of her tireless efforts and constant work overload. However, she lived to see how family law was changed in her favor with the introduction of the Civil Code on January 1, 1900. (According to the Civil Code in force until then, it was even a criminal offense to even search for the father). Now she is finally allowed to be appointed personally as guardian by the court.

On July 20, 1904, she passed away peacefully, having done her "work". Hundreds follow the funeral procession of their beloved "Tata" to the family grave. She is buried in the older rear section of the old cemetery in Bonn.

Text: Clara Wittkoepper

References

The rights to the above text are held by Haus der FrauenGeschichte Bonn e.V. (opens in a new tab)

- Schumm-Walter, Charlotte: Berta Lungstras - A Rhenish woman's life in Christian welfare (incl. portrait photo) (incl. diary excerpts 1872 to 1904), Neuwied 1932

- Wikipedia Berta Lungstras, retrieved July 16, 2020

- Hallet, Renate: Lungstras, Berta, in: Hugo Maier (ed.) Who is Who of Social Work, Freiburg 1998, p. 376f.

- Women's History Working Group/Women's Museum (ed.): Bonn Women's History - A City Tour, ca. 1987