"I am a feminist because I cannot imagine that a woman today can react to her personal experiences, the degradation caused by a patriarchal culture and a life characterized by profit, violence and boundless destructiveness in any other way than by turning to feminism. I therefore don't see women as figures of salvation, but as more sensitive and alert to strategies of self-destruction and intoxications of omnipotence." - Marielouise Jurreit

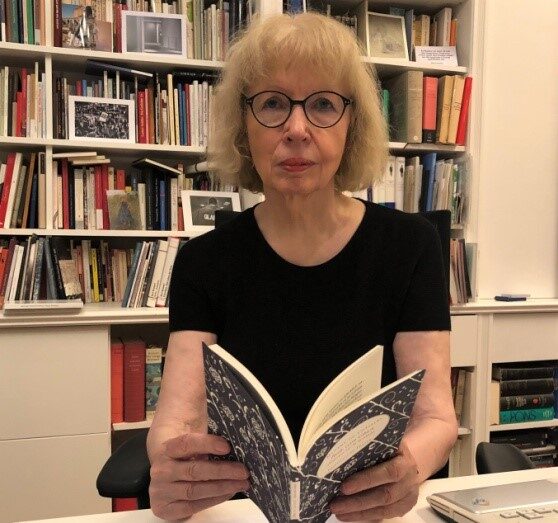

Marielouise Jurreit lived in Bonn from 1972 to 1980. It was here that she spent many afternoons sitting in the reading room of the university library on the Rhine, writing the fundamental feminist work "Sexism - On the Abortion of the Women's Question", a 700-page compendium on the history and present, theory and practice of the women's movement. The book was published in 1976, translated into English and Swedish and around 50,000 copies were sold in Germany alone.

On the one hand, the reaction - not only from the feminist press - was almost enthusiastic: "This book promises to lay the foundations for feminism all over the world." (Women's International Network News, USA), "one of the most important books, if not perhaps the most important of the German women's movement" (Courage), "certainly the most thorough, comprehensive and important publication on this subject in recent years" (Zeit), "as a basis for further discussion on the many causes of women's oppression (...) for the time being irreplaceable (FAZ), "feminist publication that must be taken seriously" (Bild der Wissenschaft), "probably the most important book on feminism to date" (Wirtschaftswoche), "a fundamental contribution to feminist theory" (Westfälische Rundschau), "total compendium of women's issues" (Neue Zürcher Zeitung), "a highly intelligent book" (Brigitte).

On the other hand, Jurreit's irrefutable analysis of the ideological foundations of patriarchal thinking is also met with tremendous resistance.

One of her main opponents is Ernest Borneman, who enjoys a high reputation on the German left and who is conducting a broad-based defamation campaign on the radio (Deutschlandfunk, WDR) and in publications as diverse as the left-wing magazines konkret and das da or the CDU-affiliated Deutsche Zeitung, in which he describes her book as a "feminist abortion" and accuses Marielouise Jurreit of having "psychological private problems". Borneman, the author of "Das Patriarchat", is on a vendetta against Jurreit, who has published a scathing review of his book in the social democratic newspaper Vorwärts. In it, she criticized "Patriarchy" as unscientific, as "the most chilling evidence of the falsification of archaeological findings". She considers his central thesis of a universal primordial matriarchy to be pure speculation. With his statements "about the sexual feelings of Palaeolithic people", he "overstepped the boundaries of research". This kind of approach puts him "close to Erich Däniken".

Here you can find out more about the woman who wrote this feminist standard work, why it is so important for women's issues and what exactly is meant by the term "sexism", which was introduced by Jurreit in Germany.

Origin and career start in Munich and Paris

Marielouise Jurreit was born in Dortmund in 1941 and grew up in a middle-class family. It was a childhood full of post-war poverty, but also full of exciting reading. Plots of rubble, where birch and lime trees sprout in the midst of the rubble, are among her earliest memories; she plays between bomb and artillery craters.

In 1960, at the age of nineteen, she moved to Munich - into the heart of the Schwabing bohemian scene, among theater and film people. She fell in love with an actor twice her age. Two weeks before the wedding, the relationship breaks up. She takes a job at the Ifo Institute for Economic Research. Then she works for almost a year in the advertising and marketing department of the Quick publishing house. In the Quick canteen, she met Traudl Junge, Hitler's secretary and a secretary to Himmler, among others, without initially learning of her role in the Third Reich. She applied to the journalism school but was rejected.

Jurreit then decided to go to Paris in 1962. She became an au pair for a rich banker's widow in St. Germain-des-Prés. Two centuries earlier, the famous Duke Saint Simon had written his memoirs, his experiences with Louis the Fourteenth at the court of Versailles and his mistresses, in her huge apartment. Madame is so stingy that Jurreit almost starved to death at the meagre lunches they share together at a four-meter-long table, sitting opposite each other at the long ends and sharing a Frankfurter sausage. She takes on other jobs, including working as an oyster saleswoman and practice assistant to a psychiatrist. To earn a little more money, she begins to write short texts that a friend of hers sells in Germany. She writes her first report for the Munich magazine Twen about her curious experiences at Madame. When she was subsequently offered a traineeship, she returned to Munich in 1964.

Journalist and mother in Munich

A few months later, Marielouise Jurreit becomes pregnant. When she informs her publisher and editor-in-chief, she is not dismissed, but told not to come into the office when her pregnancy becomes visible. Her bulging belly was not very aesthetically pleasing. In 1965, she gives birth to a daughter. The father of her child is married and her wife does not agree to a divorce. According to the law at the time (until 1977), divorce is impossible if one spouse does not agree. Also according to the law at the time (until 1970, official guardianship still applies until 1998!), as an unmarried mother she is not granted guardianship of her own daughter. She is visited every two weeks by the social welfare office, which checks whether she is fulfilling her duties as a mother. The day after the birth, a Catholic priest appears in her hospital room and suggests that she give up her newborn daughter for adoption as reparation for her 'sin'. Two hours later, a Protestant pastor appears and advises her to review her lifestyle. The result of these visits is that she does not have her daughter baptized.

As a single parent, it is hardly feasible for her to meet professional and family demands. In the editorial office, no consideration is given to her situation and she is expected to be available into the evening hours. The father of her child initially pays for a nanny, but later she is forced to temporarily leave her daughter with her mother, who lives far away, to look after her.

At Twen, Jurreit, who now works in the editorial department, has full journalistic freedom. She can choose many topics herself. In 1968, when the student revolt reached its peak, she wrote about the women of the SDS (Socialist German Student Union) and about the women's councils in Berlin and Frankfurt. She reports on the witty actions of a Munich women's commune against the police and judges and on the actions of the Dutch "Dollen Minas".

Traveling around the world

From 1966 to 1972, she undertook numerous long journeys. In Africa, she traveled to Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), in North Africa to Algeria and Morocco, and later to Senegal, Ghana, South Africa and Madagascar. In Asia, she visited Pakistan, India, Nepal, Burma, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan and the Philippines. She also traveled to Australia and New Zealand. There was no mass tourism back then. Jurreit encounters countries that have just freed themselves from colonialism. She writes reports about German women who have married an African or Asian, in which she describes how they experience their husband's home country and what the encounter with the foreign culture means to them. She enjoys writing these articles because she can include ethnological, cultural, family law and political aspects. They appear under a pseudonym in the magazine Brigitte.

Among other things, she writes reports for Twen on the 25th anniversary of the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima. In Japan, urban society is divided into hibakushas, survivors and social climbers who want to forget the bomb. She then flies to Vietnam to report on the bush war waged by the US Marines, a group of whom she accompanies on a mission and is almost killed. This genre of extensive literary reportage, enriched with background information, is almost extinct in today's media.

When she was in Pakistan on business, she had a harrowing experience when she visited a rich Pakistani family who lived on a huge estate with a few hundred family members.

"They had their own school, which only the little boys were allowed to attend, and a mosque. But above all, there was a harem, a women's wing, which the women were not allowed to leave. These women were so cut off from the outside world that no information got into their wing. (...) In the narrow alleyways of the women's wing they still had to move around veiled, even though only their husbands and cousins had access. I met twenty-five-year-olds there with large gaps between their teeth who had been constantly pregnant from the age of thirteen. They looked like matrons. Many had their arms covered with gold bracelets almost up to their shoulders. As they could be disowned at any time under Muslim law or had to put up with one or two more of their husband's wives, they constantly tried to flatter their husbands with gold. This was their reassurance in case they were sent back to their parents."

Feminism in New York

Marielouise Jurreit's key intellectual experience was reading Kate Millett's "Sexual Politics", which revolutionized her. She read the book shortly after its publication in New York in 1970 and it was published in Germany in 1971 under the title "Sexus und Herrschaft - Die Tyrannei des Mannes in unserer Gesellschaft". Jurreit's feminist radicalization is clearly evident in her polemic "Gretchen get your gun! Women are fighting in America, why not in Germany?", which she presented for discussion in Twen at the end of 1970. In this text, she also presents her own poems, alongside poems she translated from magazines of the new American women's movement, which was ahead of the European movement in terms of its feminist consciousness and self-image. Her text begins unequivocally:

"Daddy is on a death trip.

His daughters have decided to kill him.

His lovers refuse,

continue to tiptoe around his fragile ego.

His wives think he's harmful.

Daddy is overdue, his days are numbered".

Jurreit wants to encourage women in Germany to follow the example of active American feminists when she asks: "Why haven't we managed to publish our own magazines, educate our sisters, find donors, produce plays? These questions can be passed on to the female part of the Apo who do not want to open their elitist red women's fronts; to our liberal female journalists, to our female writers who are sleeping through the issue. Why are we failing like this? (...) If we wait another ten years, Daddy may be long gone and we'll still have Daddy! Gretchen, get your gun!"

At the beginning of 1971, Jurreit was the only woman to be assigned to report on the legendary world championship fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. She spends three weeks in Miami Beach at Ali's training camp. Ali loses the fight, but he still remains the greatest for half of America because of his conscientious objection to military service and his opposition to the war in Vietnam. During Ali's training, Jurreit meets half of Hollywood and TV celebrities who want to be at the fight in Madison Square Garden. Her report appears in the last issue of Twen together with Ali's drawings, which he has given her. The magazine is discontinued.

Jurreit tries to keep her head above water in New York for a few months. She also plans to publish an anthology of feminist poems by American women writers. She befriends the writer and poet Erica Jong, who also advises her on the selection of poets Jurreit should meet. Among others, she met Louise Glück, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature for her poetry in 2020. However, Jurreit was unable to find a publisher for her planned anthology.

Back in Germany, Marielouise Jurreit applies to a major left-wing magazine. Her contract was ready to be signed when the head of the department, whom she did not know, explained that it was clear that she would have to sleep with him from time to time and that he could expect a small favor from her. "I was unable to react or get a word out. I left the room without a word and felt more powerless than I had ever felt since. My whole body was shaking. It was impossible to defend myself legally at the time, otherwise I would never have gotten another job at other magazines or newspapers. I decided to work freelance from then on, trusting in my youth and my skills."

Women's movement in Bonn and Mexico City

Marielouise Jurreit came to Bonn in 1972. In the previous Bundestag election campaign, she had accompanied female candidates from all parties during their appearances. At 5.8 percent, the proportion of women in the Bundestag was at its lowest level since 1949 and even lower than in most of the Reichstags of the Weimar Republic! When Jurreit meets the elected female MPs again on their first day of sitting, some of them wander around looking for a ladies' toilet. There is only one, but men's toilets are everywhere in the building. "The numbers in the toilets shed light on the balance of power."

Jurreit stays in Bonn and is commissioned by Brigitte magazine to write a series on women's policy in the German government since 1949. She was given an interview with Willy Brandt, which appeared under the title "Do you want to be a Chancellor of equal rights?" was published in 1973. When she asks him exactly this question, he says that only history can decide, but he can already say today that no previous government in this country has done more for women. It becomes clear in this interview that Brandt is open to the emancipation of women, but does not attach any central importance to women's issues. He views the SPD far too positively when it comes to women's issues, for example when he claims that there is no other party in which the real influence of women is greater than in the SPD. And this in view of the fact that the proportion of female SPD MPs in the 7th Bundestag is 5.4 percent, which is even lower than that of the CDU! Brandt's image of women is conservative; he does not advocate the model of the woman who works all her life, but also defends the model of the housewife only. His historical knowledge of the situation of women and their struggles and demands over the last hundred years is limited to reading August Bebel's account of "Woman and Socialism".

Jurreit is asked by the Federal Agency for Civic Education to interview Elisabeth Selbert, one of the four mothers of the Basic Law, in Kassel. She spends almost three days with the lawyer, who sat on the Parliamentary Council for the SPD in 1948/49 and pushed through Article 3 of the Basic Law: men and women have equal rights. Jurreit experienced the 77-year-old as a woman with a warm personality and practical common sense, as a women's campaigner, primarily a social democrat, who did not see herself as a feminist. Elisabeth Selbert does not yet share the feminism of the new women's movement, which has a different idea of justice between the sexes and demands sexual self-determination and control over one's own body, as she comes from a different generation. After Jurreit has written three episodes on women's politics in the Federal Republic, Brigitte rejects her texts as too critical and a colleague takes over her job.

During this time, Marielouise Jurreit marries and moves to Godesberg. When she accompanies her husband to political receptions, the first question she is asked is: "What is your husband doing?" Like many women her age who, like her, feel close to the SPD but are met with a lack of understanding, she is frustrated. She became involved in the Bonn Women's Forum, a group of around thirty Bonn women who met once a week in the back room of a Bonn hotel, disappointed with Bonn's women's policy and all the parties.

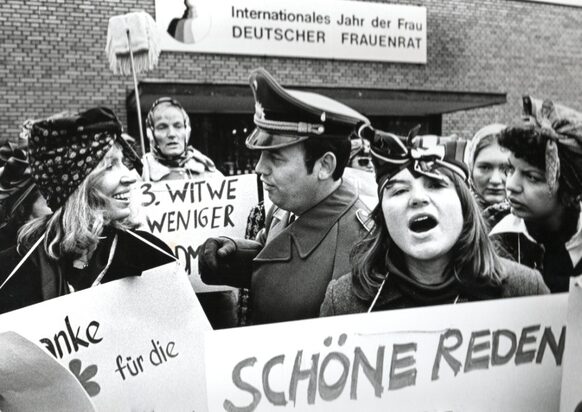

1975 is declared the International Year of Women by the UN. The Women's Forum decides on a tangible campaign for the opening event on January 9 in the Beethovenhalle, under the patronage of the President of the German Bundestag Annemarie Renger. The then Federal Minister for Youth, Family and Health, Katharina Focke, who does not want to be addressed as a minister, but only as a minister, did not invite any feminists to this celebration, but instead invited Bishop Tenhumberg and the President of the Employers' Association, Hans Martin Schleyer, as well as conservative women's associations and trade unionists!

"We dressed up as cleaning ladies with headscarves and armed ourselves with buckets, mops, frying pans and cooking spoons and chained ourselves to a railing in front of the Beethovenhalle with a fifteen-metre-long steel chain, which the guests had to walk past. We made a deafening noise and sang 'Beautiful speeches don't break our chains!" ©

They distribute an open letter to Annemarie Renger, which Jurreit has written on behalf of the Women's Forum. It reads: "We have had enough of a state in which we make up half the population, but in which we have no share. (...) We suggest that the background noise for your illustrious assembly should be the roar of children in a concrete silo of social housing (...) instead of the contemplative, discreet chamber music that you have scheduled as a supporting program. (...) The seats of the guests of honor belong to the cleaning ladies of Bonn, who clean the ministries so that an elite of men can govern, administer and oppress us." The Women's Forum's protest causes a stir, the local press reports.

Section 218 of the German Criminal Code has made any termination of pregnancy a criminal offense since 1871. In 1971, 374 women, including celebrities, confess in Stern magazine that they have had abortions. In June 1974, the governing coalition of the SPD and FDP responded to the women's movement's call for the abolition of Section 218 without replacement by introducing the 'time limit regulation'. In future, women would be allowed to have an abortion without punishment in the first three months of pregnancy after receiving health and social counseling. 193 members of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group and five conservative state governments brought an action against this new regulation before the Federal Constitutional Court. In February 1975, the court rejects the 'deadline regulation'. One of the reasons given by the court for the ruling was Germany's guilt in the Third Reich, which meant that unborn life required greater protection. It also argued that an abortion would allow the mother to get rid of a possible co-heir. The Women's Forum demonstrates against this ruling and Marielouise Jurreit reads out her open letter to Carl Carstens, then chairman of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, in front of Bonn City Hall (reprinted in: Janssen-Jurreit 1986, pp. 341-345). She writes: "This International Year of Women will go down in German history as the year in which women were incapacitated in the name of the constitution with the help of the CDU/CSU (...), in which women in the Federal Republic had to give up any hope of real equality and self-determination". It was not until 1995, twenty years later, that a constitutionally compliant regulation was found, according to which abortion remains illegal in principle, but since then prosecution has been refrained from within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy if proper counseling has been provided.

In June 1975, the first UN World Conference on Women takes place with delegations from 133 countries. The initiative for a world conference on women came from American feminists who were in close contact with female UN delegates in New York, the headquarters of the UN. No country is keen to host a women's conference. Finally, Mexico City, the capital of Latin American machismo, is found as a conference venue, which Mexico's president offers because he is flirting with the post of UN Secretary-General. Marielouise Jurreit goes there. She doesn't expect much from the official conference. Nevertheless, like other Western delegates, she is disappointed and angry that for long stretches the word 'woman' does not even appear in the discussion. The only delegation leader to oppose this is the Australian feminist Elizabeth Reid. She summarizes the oppression of women in all existing societies under the term "sexism", which must be condemned in the same way as racism, neo-colonialism and imperialism. However, "combating sexism" is not included in any of the UN resolutions; instead, the "elimination of Zionism" is included - for the first time in a UN resolution! - which makes Israeli women cry. In the end, however, the delegates, who are not really interested in the issue of women, adopt a world action plan to improve the status of women by a large majority. Shortly afterwards, the UN proclaims the decade from 1975 to 1985 the Decade of Women.

In contrast to the World Conference on Women, the Tribuna, a parallel forum of non-governmental organizations attended by over 6,000 women from eighty countries, is a "milestone in the history of women" according to Jurreit. Well-known American feminists such as Betty Friedan, Germaine Greer and Gloria Steinem are represented. The topic of 'feminism and imperialism' leads to heated discussions that last for days. Women from rich industrialized countries are confronted with the experiences of women from poor developing countries. For the first time, they hear about clitoral circumcision on women in Africa, about child brides and the murder of daughters-in-law in India, about Japanese sex tourism in South Korea, about brutal rapes in Chilean prisons and about the fact that development aid does not reach women.

"Sexism" - a new term

When Marielouise Jurreit returned from the World Conference on Women, she came up with a plan to introduce the term "sexism" to the German-speaking world. Sexism, the domination of one sex over the other, is more than just the "discrimination of women" or the "traditional distribution of roles"; according to Jurreit, it "always refers to the exploitation, mutilation, destruction, domination and persecution of women. Sexism is both subtle and deadly and means the negation of the female body, violence against a woman's ego, disregard for her existence, the expropriation of her thoughts, the colonization and exploitation of her body, the deprivation of her own language to the point of controlling her conscience, the restriction of her freedom of movement, the misappropriation of her contribution to the history of the human species." Sexism is the male monopoly on explaining the world, is the "perspective of a man's evening", the predominant view of men, which passes itself off as the general view. "Sexism is the incessant overt and subliminal degradation by the content of a male-dominated culture."

"Sexism" - a fundamental work of feminism

The publication of Marieluise Jurreit's book "Sexism" came at a time when the women's movement was expanding its activities and topics and a feminist counterculture was developing.

Numerous autonomous women's projects such as women's bookshops and publishers, women's pubs, women's health centers, self-awareness groups, etc. emerged. Feminist magazines are founded. In 1976, the first Berlin summer university took place and the first women's shelter was opened.

In Part I, Marielouise Jurreit points out the suppression of female achievements and liberation struggles in historiography. This leads to women not relating history to themselves at all and to women identifying with male actors and their values. In Part II, she refutes the thesis of matriarchy as the original state from which patriarchy emerged and proves that the oppression of women existed before the emergence of private property. In Part III, she deals with the dispute between feminism and socialism and uses examples to demonstrate that 'class liberation' primarily meant male liberation. In Part IV, she demonstrates that the achievement of women's suffrage did not lead to the emancipation of women, but actually contributed to the failure of the first women's movement. Part V deals with the question of the non-natural

gender-specific division of labor and the invisibility of housework. Part VI deals with sexuality and reproduction as well as the cult of the mother as an instrument of oppression. In Part VII, she demonstrates that physical violence against women must be seen as a general characteristic of human society. Part VIII examines the consciousness structures of sexism such as role stereotypes and language, the "genitals of speech". In the final part IX, Jurreit outlines goals and strategies for a future feminism.

Marielouise Jurreit begins her book with a comparison of Hedwig Dohm and Katia Mann, grandmother and granddaughter of a family that are worlds apart. Hedwig Dohm (1833-1919) was the most radical women's campaigner of her time. With a sharp pen, biting mockery and clear-sighted analysis, she fought for the complete emancipation of women and, as early as 1876, called for women's suffrage as the goal of all women's struggles, as a "step across the Rubicon". This instrument of power was the basis for improving marriage, school and employment law in the interests of women. Her granddaughter Katia Mann (1883-1980), wife of the writer Thomas Mann, did not include her grandmother's revolutionary ideas and radical insights in her memoirs. Her memoirs contain statements that her grandmother would have considered misogynistic and unreflected. She begins her notes with the sentence: "My father was a professor of mathematics and my mother was a very beautiful woman." She omits her mother's profession, who was a renowned actress. Or she mentions how uncomfortable she always felt giving birth to daughters. She broke off her studies - she was one of the first generation of female students in Germany - in 1905 because of her marriage, much to the regret of her grandmother, who had fought all her life for the right to a university education for women.

This piece of family history shows how feminist insights could seep into the same family within two generations, and at the same time reflects the decline of the first women's movement, which disappeared without a trace with the introduction of women's suffrage and even fell into oblivion. Instead, after the introduction of voting rights for women, the term "equal rights for women" only conceals the fact that the balance of power between men and women did not fundamentally change. At least it was possible to point to small improvements and reform steps. Marielouise Jurreit summarizes: "The political struggle of women in the last century failed because they were only able to achieve formal rights for their daughters and granddaughters. The first international women's movement did not succeed in destroying the androcentric perspective, in which the man is at the center of all social considerations."

A few typical quotes from Marielouise Jurreit's interviews with members of the 7th Bundestag may illustrate what is meant by "equal rights in the patriarchy" in the early 1970s:

"As a man, I find it more pleasant now to work with female politicians who have a little more charm, who can lead us over to liberal family policy, instead of these frustrated demands for emancipation. We need specialist politicians and not women politicians in the party." (FDP)

"The last three generations of bluestockings have not been particularly exciting. There are more complete tasks than the fight for women's rights." (SPD)

"In the past, far too many women went into politics because it didn't work out with the male sex. The percentage of women who have a physical disability in state and local politics is disproportionately higher than that of men who have a physical defect." (CDU)

"I have something against the partout women who raise their fingers and come forward and start, we women ... My wife is dear to me in my own four walls, but not in meetings. (...) Mrs. Brandt, she does it skillfully, she shines with beauty - she doesn't embarrass her husband." (CSU)

What fascinates me most about Jurreit's "sexism" study is how she describes the glory and misery of the first women's movement and the reasons for its decline. This is how Rita Süssmuth assessed the book in 1989:

"Seen from today's perspective, this overall analysis of patriarchy is just as correct as it was then. Since 1976, many topics have been examined in greater detail and reappraised by the increasingly established field of women's studies, and Marielouise Janssen-Jurreit's interpretations have certainly been confirmed. And it is still true today: anyone interested in coming to terms with the history of women and a thorough analysis of the phenomenon of "sexism" is still recommended to read this exciting, well-written fundamental work.

More feminist books

One point of criticism from the women's movement regarding her "sexism" study was the lack of solutions. Marielouise Jurreit responded to this in 1979 with her book "Frauenprogramm" (Women's Program), in which she, as editor, brought together almost forty female authors who were experts in their field and supported the women's movement. It is a careful inventory of the legal situation in Germany as well as factual and indirect discrimination against women. The result is depressing. Although equality between men and women is enshrined in the Basic Law, it does not correspond to reality. "Frauenprogramm" does not stop at the balance sheet alone, but also makes concrete reform proposals in the areas of education and advertising, for training, job allocation and pay, against unequal treatment by public employers, for taxes and pensions, against sexualized violence, against discrimination against lesbian women, for the conditions of women in prisons and for the dismantling of structural barriers in trade and agriculture. Jurreit envisioned bundling all these feminist demands into a joint action plan.

In 1986, Jurreit publishes another feminist book, "Women and Sexual Morality", which focuses on the sexual question as the most explosive issue for the women's movement. Because: "The reason for the oppression of women in all societies, for the emergence of patriarchal structures, lies in the male control of female sexuality and fertility." For the most part, texts from the old women's movement are reprinted and made accessible again, which had fallen into oblivion because they were missing from the history books. The main focus is on the issue of abortion and contraception, but it also deals with prostitution, double standards, illegitimate motherhood and sexual violence. Texts from the new women's movement broaden the spectrum. The historical line of the women's struggle is thus documented and similarities and differences become visible.

Shadows of totalitarianism in Munich and Berlin

In 1981, Marielouise Jurreit leaves Bonn with a heavy heart and moves to Munich with her husband because of his professional career. She separated from him in 1983. She works as a freelance writer for Stern, Spiegel, Süddeutsche Zeitung and Brigitte. She is denied a permanent position in journalism because she is labeled as a writer of sexism. She is considered a "professional feminist", which she never wanted to be. Everywhere she appears, feminist utopias are demanded of her. However, she sees herself more as a critic and skeptic, for whom analysis and the fight for goals are more important than fantastic

fantasies of the future.

She therefore turned to another topic that preoccupied her, the question of Germans' fragile identification with Germany, their disturbed, wounded sense of national identity. In 1985, she published the book "Lieben Sie Deutschland? Feelings on the state of the nation". Jurreit hoped that the statements of over forty men and women in this volume would provide "insights into the web of contradictions, idealizations, rifts, sensitivities, absurdities and neuroses that determine our relationship to this country."

In August 1989, Marielouise Jurreit meets female war veterans in Poland who fought in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 and activists from the 1980s, without whom the independent trade union Solidarnosc would not have been founded. In her comprehensive report "Madonna and Heroine", she documents how women organized the high-circulation underground press and wrote articles under male pseudonyms - a fact that is still known to few today. As a result, and because those in power did not have enough imagination to even imagine female resistance, they were not suspected of being women by the regime.

On November 11, 1989, Marielouise Jurreit flew to Berlin to witness the opening of the Wall in person. That same weekend, she decided to move to Berlin to witness the changes on the ground. In 1990, the year of German reunification, she feared the rise of nationalism, as frustration would be inevitable when painful economic transformations and social upheavals occurred. In her article "German Unity and Women - Some Long Overdue Remarks", she complains that the situation of women had been completely ignored during reunification.

During the 1991 Berlinale, she met her future partner Hanns Eckelkamp, the owner of several film companies in Duisburg. She initially had a weekend relationship with him, but today they live next door to each other in Berlin. When his company got into difficulties, Jurreit took over the management of the legendary Atlas Filmverleih from 1994 to 1998. This made her solely responsible for the program and management. With "Nightwatch", a funny movie between thrill and horror, she reaches audience figures of almost one million.

million.

In the fall of 2000, her first novel "The Crime of Love in the Middle of Europe" is published, which is number one on the Südwestfunk's bestseller list in February 2001. Berlin is meant by "the center of Europe". This phrase originates from the negotiations on the Eastern treaties. The West German representatives used it because the Soviet and Polish governments did not allow the word 'Berlin' to be mentioned. Her novel is about a hopeless love story against the backdrop of a family history that suffered the political catastrophes of the 20th century (National Socialism and Stalinism, later Soviet Communism). Nori, the first-person narrator, a historian, lives in Bonn as the wife of a senior civil servant in the Federal Press Office. She and her lover Adam, a Polish intellectual, meet in a basement apartment in Berlin. The two protagonists are traumatized by the post-war period in their respective countries. Their love fails after martial law is declared in Poland due to the East-West conflict.

Her second novel "The Proposal", set in the theater and film milieu in Berlin, was published in 2004 and is about the aging television star Harry, who by chance is able to buy the Berlin apartment in which he lived as a post-war child. This marks the beginning of the unstoppable regression of the anti-hero. In this apartment, as a boy, he secretly watched the love scenes of his Nazi father, who cheated on his mother for years. At some point, the son snitched on his father, whom he never saw again after he moved out. When the seriously ill, very young drama student Katja makes him a clear offer to sleep with him, an obsession begins in which Harry relives his father's passion for love in order to absolve himself of his betrayal. Katja is portrayed with self-confidence, she sets the scene in contrast to many women in this scene who have been sexually harassed and have reported it under "MeToo". This novel is not about love, but more about sex and death. Marieluise Jurreit knows how to break down gender clichés and unmask male fantasies as such.

Conclusion

In her book "Sexism", Marielouise Jurreit advocates feminist self-organization of women outside of institutions such as political parties and trade unions. Autonomous women's groups were necessary in order to develop a self-confident identity of their own and to integrate women's history into their self-image. The independently organized new women's movement actually achieved a great deal between 1975 and 1985. Jurreit herself sees it the same way: "Nevertheless, this last decade has been a triumph for women, comparable only to the heyday of the international women's movement between 1900 and 1914." Who could have expected that feminism would even reach the political parties? The proportion of female MPs in the current Bundestag is over thirty percent (although it has fallen by almost 6 percent compared to the previous Bundestag!) and feminist speeches are even being made in the Bundestag today.

However, according to Marielouise Jurreit, the "key industry of every society", the raising of children, is still demanded as motherly love and not economically rewarded, although the "production of the next generation" is indispensable for the continuation of society. Childcare and upbringing is the most time-consuming activity in any human society. In view of this, all family policy measures - such as maternity protection, parental and child benefits or maternal pensions - seem like charitable donations. A real price must be found in our economies for the amount of time and work involved. Female part-time work, a lack of careers and poverty in old age are the consequences of our social order. As long as this "key industry" of ours is not calculated and rewarded economically - "priced" - real equality cannot be achieved.

Text: Ulrike Klens

References

The rights to the above text are held by Haus der FrauenGeschichte Bonn e.V. (opens in a new tab)

Marielouise Jurreit (also Janssen-Jurreit):

- Sexism. On the abortion of the women's question. Munich 1976

- (ed.): Women's Program. Against Discrimination. Hamburg 1979

- (ed.): Do you love Germany? Feelings on the state of the nation. Munich 1985

- (ed.): Women and sexual morality. Frankfurt am Main 1986

- The crime of love in the center of Europe. Berlin 2000

- The proposal. Frankfurt am Main 2004

- Who is still afraid of Hiroshima?, in: Twen. August 1970

- Surviving Vietnam: Tell Charlie we're going home!, in: Twen. September 1970

- Women are fighting in America. Why not in Germany? Gretchen, get your gun!, in: Twen. November 1970

- Do you want to become a Chancellor of equal rights?, in: Brigitte 19/1973

- Review of Borneman's book "Das Patriarchat", in: Vorwärts. November 1975

- Before the II World Conference on Women in Nairobi, in: Brigitte 13/1985

- Madonna and Heroine - Poland's women in the struggle for independence and human rights 1989, in: Brigitte. November 1989

- German unity and women - some long overdue remarks, in: Brigitte, November 1990

- Ernest Borneman: Feminist abortion, in: konkret 1/1977

- Ernest Borneman: No anger and no vindictiveness (letter to the editor), in: konkret 3/1977

- Rita Süssmuth: "Sexism" criticism and women's politics, in: Feminin-Maskulin. Friedrich Jahresheft VII, Hanover 1989, p. 69 f

- Emails to Ulrike Klens from October 2020 to January 2021